Watch here!

Continue reading Teach-In on RAD in the RockawaysMonthly Archives: March 2022

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start writing!

How did we get here?

Public housing in the United States is in grave and worsening disrepair. Today, the fiscal cost for addressing the national housing stocks’ critical repair needs is estimated to be between $70-80 billion, with New York City alone requiring about half that amount. More specifically, the latest figures proliferated by NYCHA at various hearings are $31.8 billion over the next five years, and $45.2 billion over the next twenty.

These figures today are the exponentiating outcome of underfunding and inaction over time, which grows the cost of the problem in New York City by about $700 million a year and has left at least 42,000 units needing at least $200,000 in repairs (Moses, 2018). What this has meant is that despite spending $2 billion on NYCHA’s capital repair needs from 2011 to 2017, estimates for NYCHA’s needs grew exponentially from $1.6 billion to $25 billion (Moses, 2018). Further, the growing disrepair threatens the future of the housing stock altogether, which in turn presents greater risks to residents. As it stands now, between 8,000 and 15,000 units nationally are condemned every year due to disrepair (Human Rights Watch, 2022). Further still, as the problem has been mounting, funds have been drying up further: “in real terms, funding for public housing was 35 percent lower in 2021 than it was in 2000” (Human Rights Watch, 2021).

This is alarming given that public housing is a critical form of affordable housing for wide variety of economically-vulnerable households nationally, and especially in the tightening housing markets like in NYC. As Table 1 shows, the average income of public housing residents in New York City hovers around $25,000, more than half are not in the workforce, and nearly half rely on some form of government assistance (NYCHA, 2019; 2021). On average, they are among the city’s “extremely low-income” households, the vast majority of whom are severely cost-burdened (if they are able to afford housing at all), and struggle with ongoing housing insecurity. For many of these households, the loss of their unit would deepen our dual housing and humanitarian crisis at both the household and city level.

RAD is the federal program that was created in response to this crisis, which has been adopted locally in NYC as the RAD/PACT program.

Know what RAD is? Return to the homepage to explore the evaluations and perspectives on the program.

Introduction to RAD & RAD/PACT

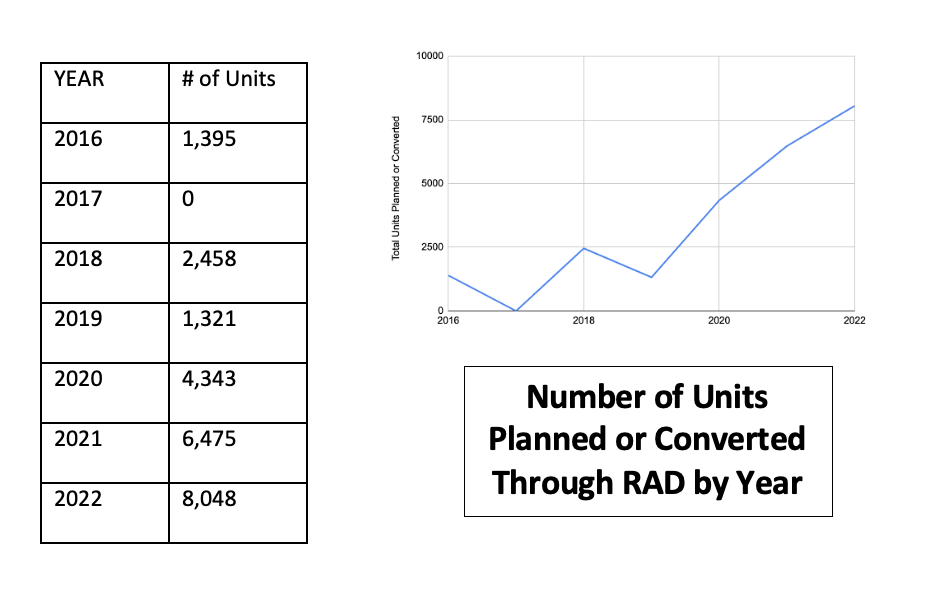

Rental Assistance Demonstration or RAD is a federal program that was designed to address the deterioration of our national public housing stock. In short, the program allows public housing authorities to shift all or some of their public housing stock to a different federal subsidy stream, which also allows for private partners to step in to manage or finance the properties. The program was approved by Congress in 2012 under the Obama Administration, and implemented by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) beginning in 2013. Though conceived of as an experimental program with a limit of 60,000 units, the program expanded rapidly with public housing authorities of all shapes and sizes and geographies applying to convert all or part of their portfolios to the RAD program. Today, the limit is set at 455,000 or nearly 40% of all public housing units nationally.

RAD/PACT in NYC

RAD first arrived in New York City (NYC) in 2015 and has proceeded at a similar pace. NYC’s uniquely-branded program, Permanent Affordability Commitment Together (commonly known as RAD/PACT) was first introduced as one of a few strategies for public housing outlined in Mayor’s De Blasio’s first plan for public housing, NextGeneration NYCHA, and greatly expanded in a subsequent iteration of the plan, NYCHA 2.0. Specifically, while the original 15,000-unit-pipeline was whittled down to a meager 1,700 units through the application and approvals process, NYCHA 2.0 expanded the pipeline to 62,000 units, with a third of those to be converted by the end of 2022.

Evaluations are Lagging, and Mixed, at Best

Officials evaluations of residents’ experiences of RAD conversion have not kept pace. Specifically, HUD’s 2016 report excluded resident perspectives entirely. After an evaluation by the Government Accountability Office in 2018 highlighted HUD’s lack of attention to resident experiences, HUD did include a resident evaluation in their 2019 report. While their assessment yielded positive reviews, their sample was irresponsibly small – less than 1% of households whose homes had converted by October 2018.

Meanwhile, independent evaluations are largely negative. The most significant study is also the most recent. In 2022, Human Rights Watch released an assessment of public housing and RAD in New York City which highlighted two key findings:

- RAD conversion had resulted in higher evictions at two of the six developments evaluated (Betances and Ocean Bay Houses)

- RAD lead to greater violations of tenants’ rights and protections.

In 2021, based on this research, they sent a letter to Congress demanding the fund public housing through Section 9 immediately.

What Next?

Review a presentation from March 29th, which gave an overview of some of the key evaluations, or return to the homepage and explore the evaluations for yourself!